“Evidence Based Policy Making” or “Evidence Informed Policy Making”?, by Stephen Gregory

Stephen Gregory is the Library Enquiry Services Manager in Welsh Government Information, Library & Archive Services. Stephen is also the Honorary Secretary to the Government Information Group Committee. He writes in a personal capacity.

This blog post considers how

language surrounding the use of evidence for the creation of governmental

policy may be evolving and specifically looks at the use of the phrases

Evidence Based Policy Making (EBPM), Evidence

Based Policy (EBP), Evidence Informed Policy Making (EIPM) or Evidence Informed

Policy (EIP). The prevalence of these phrases in one bibliographic database is

explored. This leads to the conclusion that it may be time to reappraise our

own use of this terminology in the workplace and professional literature.

The Past

When I joined GKIM as a policy

support librarian in a UK devolved administration in 2006, my librarian

colleagues, as well as government social researchers and policy officials

frequently referred to EBPM. At the time, perhaps naively, to me EBPM offered

an exciting arena for government knowledge and information management (GKIM)

specialists and as well as government analytical professionals (social

researchers, statistician, economists and cartographers) to provide policymakers

with evidence to support effective policy-development. Through the provision of

the best published evidence, I felt that I could really help to make a

difference. At the time we recognised that policy implementation and change

will always have a political dimension. The political colour of the government

of the day naturally determines the palatability or otherwise of certain policy

initiatives. We also recognised that other factors were also in play: financial and

sociological / societal. But somehow these weren’t directly encompassed in the

EBPM terminology. They remained latent factors.

|

| Nick Youngson / Licensed by R M Media Ltd under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license available from https://www.picpedia.org/post-it-note/e/evidence-based.html. |

Corridor Conversation

Fast-forward to 2023 and a corridor

discussion with a policy official. We were chatting about how evidence is used

in policy making, and out I trip with the phrase “EBPM”. The official very gently

and kindly explained that my terminology was a little dated, and that it may

now be more appropriate to refer to “Evidence Informed Policy Making” (EIPM).

He rehearsed the argument that policy development may be informed by published and

other forms of available evidence. However, additional factors enter the policy

change mix, including a Minister’s political leanings, as well as significant factors

such available funding, competing government priorities, societal issues, and potentially

in the UK devolution context, whether a government has powers to make such

changes.

The change in terminology to

EIPM was a revelation and I am so grateful for that conversation! I have since

shared this with my work colleagues and at a recent Government Information

Group committee meeting. In both cases colleagues were grateful for the

opportunity to explore this potential change in terminology. A great reason for

this blog posting!

Echo Chamber?

I then began to wonder if I

had been stuck in a terminology echo-chamber; a sealed black box? How had I not

picked up on this terminological change sooner?

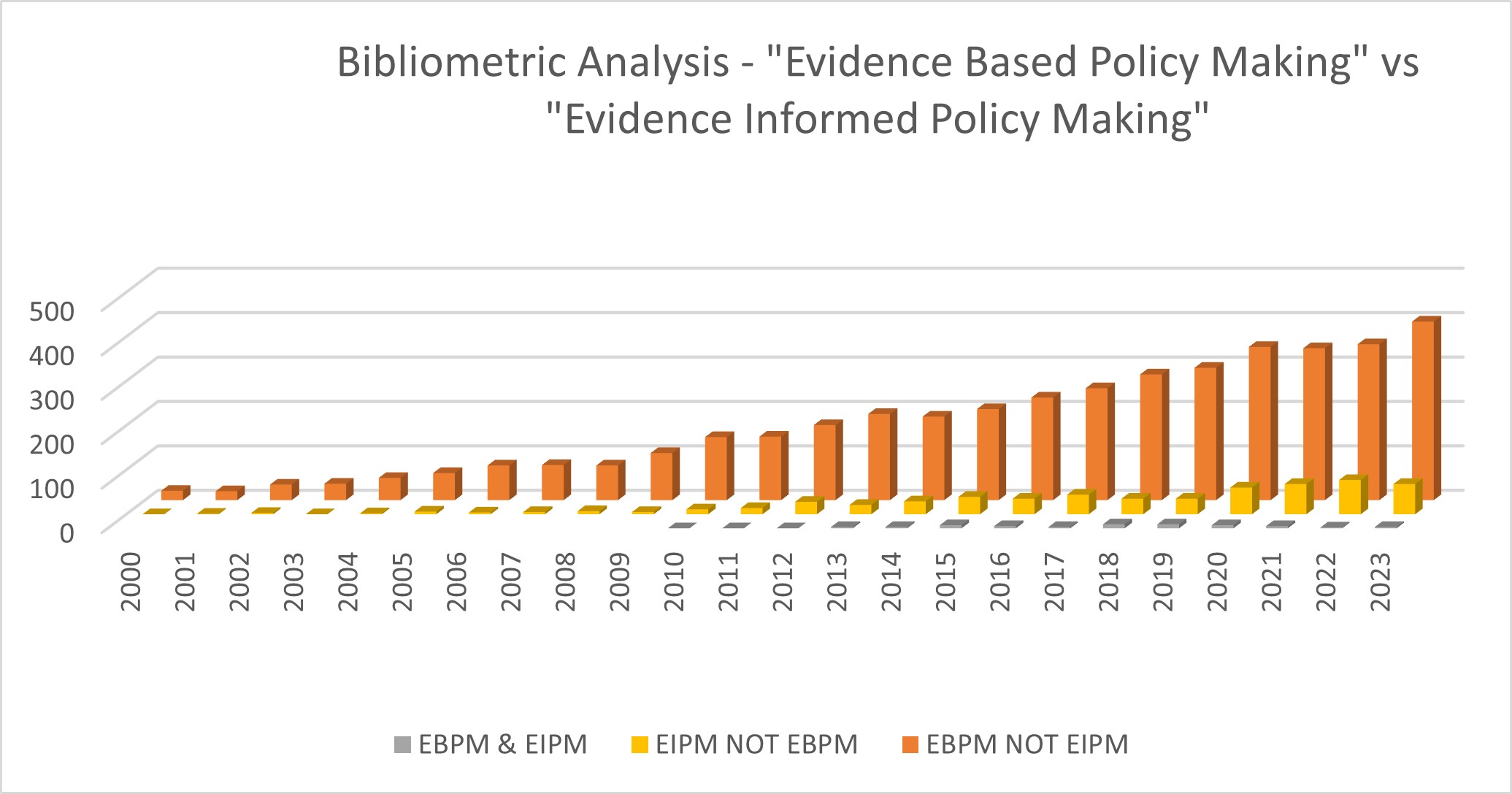

An analysis using Elsevier’s Scopus database reassuringly suggests

otherwise. It appears that specific reference to EBPM continues to predominate

in the published literature. The phrase “EBPM” first appears in the Scopus

database (in title, abstract or keyword fields) in 1997, with gradually

increasing frequency throughout the early decades of the 21st century.

In 2023 in the Scopus database there are 402 citations quoting the phrases EBP

or EBPM in these fields, and which do not also refer to EIP OR EIPM. The phrase

EIPM does not appear in the Scopus database, in the previously mentioned

database fields, until 2001. EIPM / EIP start from much lower frequencies, in

Scopus at least, and have a slower and more gradual increase in usage. In 2023,

68 Scopus citations included EIPM or EIP, whilst also specifically not

referring to EBPM or EBP. A small number

of citations indexed in Scopus refer to both EBPM / EBP and EIPM / EIP, with

this occurring from 2013 onwards. The bar chart illustrates these trends

(Figure1).

|

Figure 1. Frequency of EBPM or

Evidence Based Policy, and EIPM or Evidence Informed Policy in the Scopus

database, Title, Abstract or Keyword fields, 2020-2023 (Data at 14 January

2024).

So, the literature indexed in

Scopus demonstrates the continuing predominance of EBPM, and a gradual rise of

EIPM. I have only researched the bibliometrics in Scopus. Grey literature or

monographic sources may tell a different story, but I suspect not.

So what?

My experience indicates that EBPM was always understood as including elements of political, sociological and economic reality, it’s just that these elements remained hidden or blind within the terminology. Recently, the European Parliamentary Research Service recognise the sociological aspects in the application of EBPM whilst retaining the phraseology:

“This paper deals with 'evidence-based policy-making', as it uses the best available scientific evidence to formulate policies. However, 'evidence-based policy-making' does not imply that policy decisions should be taken solely based on scientific evidence. Policy decisions based exclusively on scientific evidence are technocratic, which is not a policy's aim in a parliamentary democracy. Democratic policy-makers usually combine the best available evidence with their understanding of a society's needs, i.e., contextualising the evidence in terms of what they believe is in accord with the citizens' expectations, values and preferences.” Source – EPRS. Evidence for Policy Making. European Parliament, March 2021. PE 690.529. [accessed on 14/01/2024].

The bibliometric analysis from

Scopus demonstrates that we are likely to continue to experience the use of

EBPM or EBP in our professional reading, and no doubt, within discussions. When

we do, we might do well to personally reflect on, and acknowledge, the latent political,

economic, and sociological factors that may also influence, moderate or refute

the application of the evidence in the provision of new or reformed policy, or

indeed in the decision to make no change, to leave things as they stand.

In our own conversations and writings,

it may be more appropriate, transparent, and therefore more accurate to talk in

terms of EIPM or EIP. In doing so we may help others to consider the wider

range of influences involved in governmental policy making, whilst still

valuing the role that GKIM and government analysts can, and do play in

supporting governmental policy design, reform, and evaluation processes.

Get in touch!

Hopefully this blog has helped

you review your terminological use and understanding? We are keen to hear about

your experiences. Does this resonate with you? Are there additional considerations

or perspectives that need to be taken on board?

Comments

Post a Comment